The Great Outdoors: The History of Recreation in Marquette County Special Exhibit

|

Bicycling | Birding | Cross Country Skiing | Dog Sled | Downhill Skiing | Guts Frisbee | Ice Skating | Luge | Paddling | Rock & Ice Climbing | Running | Scuba Diving | Ski Jumping | Snowshoe | Trails | Wildlife Photography

|

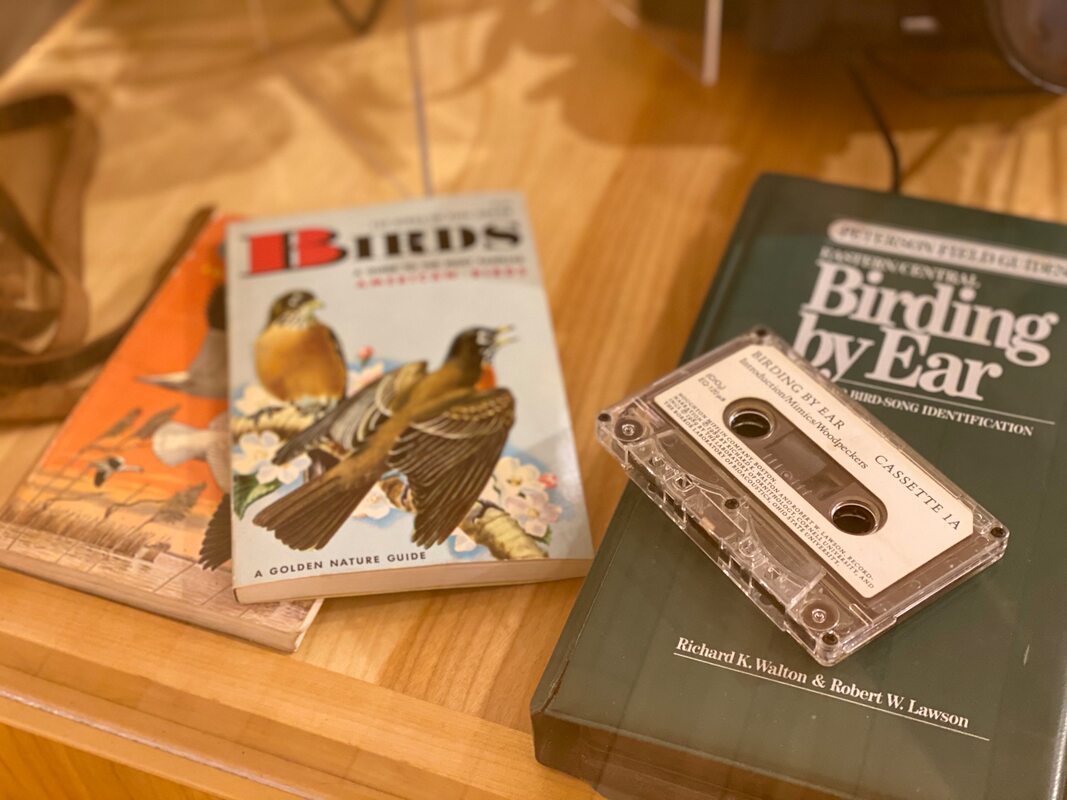

Birding is a very simple outdoor activity to begin. An identification guide and binoculars are the only necessary equipment. One can start in one’s backyard and nearby parks, but may also travel. Though birding may be a solitary activity, it can also be social with clubs, programs and activities.

The Laughing Whitefish Audubon Society serves Marquette and Alger Counties. Its mission is to raise public awareness of the importance of natural wildlife and other natural resources, to promote interest in native birds and their habitat and to help the National Audubon Society in study, conservation and research. The local group has met since 1992.

Bird counts are an opportunity for birders to practice their skills and help conservation efforts. On Brockway Mountain in the Keweenaw the Copper Country Audubon Society counts raptors each spring with help from the Laughing Whitefish Audubon Society.

The Laughing Whitefish Audubon Society serves Marquette and Alger Counties. Its mission is to raise public awareness of the importance of natural wildlife and other natural resources, to promote interest in native birds and their habitat and to help the National Audubon Society in study, conservation and research. The local group has met since 1992.

Bird counts are an opportunity for birders to practice their skills and help conservation efforts. On Brockway Mountain in the Keweenaw the Copper Country Audubon Society counts raptors each spring with help from the Laughing Whitefish Audubon Society.

The National Audubon Society began a Christmas bird count in 1900 in order to create an alternative to competitive shooting of birds at that time. Marquette has held a Christmas count since the 1940s. The count covers a 7.5 mile radius (from downtown Marquette). Birders spend a day at a variety of sites and habitats, including some backyard feeders to count the number of species and the total number of birds. A count of 50 species or higher is considered a good year for our area.

Christmas counts are also done in AuTrain and Gwinn. In 2015 Gwinn counted 1000 individual birds and 28 species. The number of species is up since the 1980s: then Gwinn averaged 20. Since 2002 the average has been 25.

The population of bald eagles in Michigan and the UP was threatened for several decades. Herbicides and pesticides are thought to have caused the low numbers. In 1980 82 pairs were counted statewide. By 1996 this number had grown to 285 pairs statewide, with 2/3 found in the UP.

Christmas counts are also done in AuTrain and Gwinn. In 2015 Gwinn counted 1000 individual birds and 28 species. The number of species is up since the 1980s: then Gwinn averaged 20. Since 2002 the average has been 25.

The population of bald eagles in Michigan and the UP was threatened for several decades. Herbicides and pesticides are thought to have caused the low numbers. In 1980 82 pairs were counted statewide. By 1996 this number had grown to 285 pairs statewide, with 2/3 found in the UP.

Wildlife Photography

George Shiras III (1859-1942) is considered the inventor of nighttime photography and a pioneer of wildlife photography in general. His family had a camp on Whitefish Lake in Alger County where he took many of his photos. Shiras grew up in Pittsburgh. He followed his grandfather and father’s footsteps into law and politics and into the Northwoods to go hunting and fishing. George’s grandfather came to Marquette to go fishing in 1849. The family continued coming to the area to hunt, fish, and enjoy the area while Marquette grew. The Shirases hunted with local settler and businessman Peter White (1830-1908) on his Whitefish Lake property.

French-Indian guide Jack LaPete took eleven year old George Shiras III and his younger brother Winfield out to Whitefish Lake in 1870 long before a road, railroad or even path were established there. George’s sense of adventure and love of hunting turned into a passion for wildlife photography and study.

Please visit our main exhibit gallery for examples of Shiras and Hammer’s equipment and work.

French-Indian guide Jack LaPete took eleven year old George Shiras III and his younger brother Winfield out to Whitefish Lake in 1870 long before a road, railroad or even path were established there. George’s sense of adventure and love of hunting turned into a passion for wildlife photography and study.

Please visit our main exhibit gallery for examples of Shiras and Hammer’s equipment and work.

Pictured here from left is Jack LaPete, Lord Brassy, George Shiras III, Peter White, and Fred Cadote at Fiddling Cat, Whitefish Lake.

Peter White and the Shirases built a hunting camp there together in 1880s. George III married Peter White’s daughter, Fannie, in 1885. George continued to live in Pittsburg but spent much of his summer and part of the fall in Marquette and at the camp. He served as US Representative and helped draft the Migratory Bird Act.

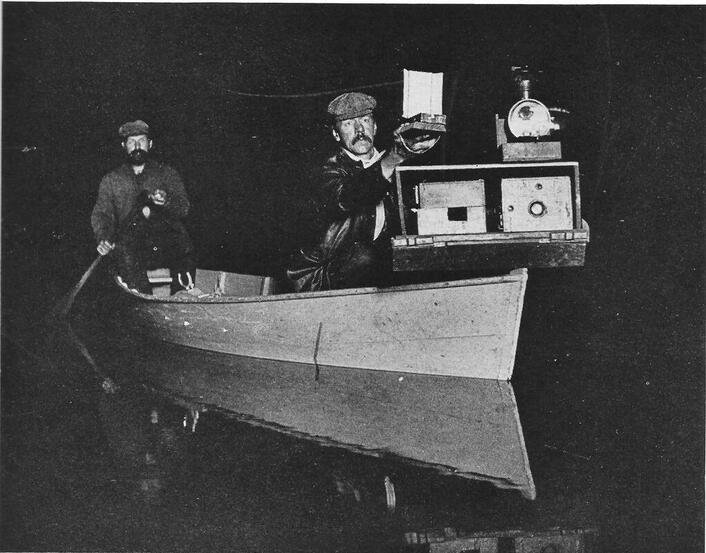

Shiras began working with John Hammer in the mid 1880s to develop methods for animals to take their own picture. Hammer had experience at an optical factory and worked in Marquette at an engine works. They used trip wire, a baited wire, and took nighttime flash photographs of wildlife.

In the boat, Hammer navigated through the dark waters and Shiras took the bow to operate the photographic equipment. Pictured here in 1893.

The method was based on the idea of “shining” a deer and shooting it when it froze in the lights. Hunters had often used this technique which was based on the local Ojibwe hunting practice of burning pine knots.

In 1906 the National Geographic Society published over 900 of Shiras’ day and night photos primarily from the UP. His work won numerous awards and he eventually published a two volume book, Hunting Wild Life with Camera and Flashlight, at the encouragement of Teddy Roosevelt.

Shiras began working with John Hammer in the mid 1880s to develop methods for animals to take their own picture. Hammer had experience at an optical factory and worked in Marquette at an engine works. They used trip wire, a baited wire, and took nighttime flash photographs of wildlife.

In the boat, Hammer navigated through the dark waters and Shiras took the bow to operate the photographic equipment. Pictured here in 1893.

The method was based on the idea of “shining” a deer and shooting it when it froze in the lights. Hunters had often used this technique which was based on the local Ojibwe hunting practice of burning pine knots.

In 1906 the National Geographic Society published over 900 of Shiras’ day and night photos primarily from the UP. His work won numerous awards and he eventually published a two volume book, Hunting Wild Life with Camera and Flashlight, at the encouragement of Teddy Roosevelt.

Photographic Equipment has changed dramatically in the last 100 years. Before film, large box cameras were loaded with plates. Cameras were large and awkward to use.

In the below slideshow below you will see:

An Eastman No. 2 Box Film Camera, 1899

J.M. Longyear would have used something like this camera. It look 3 ½” circular images. The shutter was manipulated by a string. It could hold 60, 100, or 160 exposures of film. The whole camera was sent back to the factory for de veloping and reloading of film.

Circular Photograph by J. M. Longyear

Timber land and mine developer John Longyear (1850-1922) was an avid photographer and took many landscape photos of the area.

An ICA, Dresden, Germany Folding Camera

circa 1925 This camera belonged to George Shiras III. Cameras became more portable and affordable in the 1920s.

A Kodak 35 Rangefinder from 1948; a Bakelite Brownie Hawkeye, Kodak from 1949-1961; a Konica Ft-1 Electronic Camera, 1982-87; stereographic photos by George Shiras III

Scot Stewart

Scot is a middle school science, world history, and photography teacher. He has written a column on birds for twenty years for the Mining Journal and has written about general science and history for the Marquette Monthly for five years. Scot and his wife Corrine Rockow were instrumental in starting and are still involved with Moosewood Nature Center. Scot says his interest in wildlife photography grew slowly:

I think I first got interested in wildlife about first or second grade. Had a bird book about that time. Got interested in a lot of other things like insects in seventh grade and minerals in ninth grade. Got my first camera, just a little Brownie, I think, around freshman in college. But I discovered the Sierra Club coffee table books. They had a whole series of just ginormous books, Ansel Adams and Elliot Porter, just all the great outdoor photographers of the time. So, I spent hours poring through stuff at Northern [Michigan University’s] library. Then discovered Audubon Magazine and they had a number of photo essays in each issue. Those are what really hooked me on photography. Scot Stewart

In 1970 he took a class at NMU's Free University. George Wilson taught a photography class using wolf cubs he was raising. The wolves got Scot's attention. George filmed the four wolf pups and took Scot under his wing as his assistant. At the time, it was some of the best wolf footage in the world.

Scot is a middle school science, world history, and photography teacher. He has written a column on birds for twenty years for the Mining Journal and has written about general science and history for the Marquette Monthly for five years. Scot and his wife Corrine Rockow were instrumental in starting and are still involved with Moosewood Nature Center. Scot says his interest in wildlife photography grew slowly:

I think I first got interested in wildlife about first or second grade. Had a bird book about that time. Got interested in a lot of other things like insects in seventh grade and minerals in ninth grade. Got my first camera, just a little Brownie, I think, around freshman in college. But I discovered the Sierra Club coffee table books. They had a whole series of just ginormous books, Ansel Adams and Elliot Porter, just all the great outdoor photographers of the time. So, I spent hours poring through stuff at Northern [Michigan University’s] library. Then discovered Audubon Magazine and they had a number of photo essays in each issue. Those are what really hooked me on photography. Scot Stewart

In 1970 he took a class at NMU's Free University. George Wilson taught a photography class using wolf cubs he was raising. The wolves got Scot's attention. George filmed the four wolf pups and took Scot under his wing as his assistant. At the time, it was some of the best wolf footage in the world.

|

When Scot moved to Marquette in 1969 there wasn't much going on with wildlife photography in the community. In the 1980s a photography club formed but many members were landscape photographers. Local professional photographers were doing studio/ portrait photography. However there was Beauchamp’s camera shop downtown which provided equipment.

One of Scot’s early starts with wildlife photography was at the deer pen at Presque Isle, a 2 1/2 acre fenced area with about 24 deer and an albino buck (the first albino in the area). Many nearby areas had wildlife and scenery he would photograph: Presque Isle, Pictured Rocks, 510, 550, there’s just a ton of lakes and creeks that are just gorgeous, spectacular spots and along the way there’s usually lots of wildlife to see. The Harlow Lake area is just a wonderful spot. Laughing Whitefish Falls, I found not only had the falls but lots of great wildflowers and birds there. It was places close to home, really, where I got started. Scot Stewart Northern Hawk Owl photograph by Scot Stewart |

When Scot was just starting out he also had a unique opportunity. Photographer Jim Wuepper also raised some wolf cubs. Jim, Scot and George Wilson all took care of them.

I had an opportunity a couple of times, in the springtime, to explore their dens. One year, they had a den that was about 24 feet long and dropped down between three and four feet. Their pups were born usually the first week of May. So, it was still a time when there was frost on tree roots and things like that but I crawled down a couple times into wolf dens and would take my flashlight and then a bag with my camera and flash in it because it didn’t fit. I dragged the thing through and literally kind of crawled on my belly down these twenty some feet while Jim stood at the top of the opening, and got down to where the pups were and took pictures of the pups. Had a chance to really get to know how the wolves behaved. Eventually we had to pass them on to another location but it was just a phenomenal opportunity to photograph. It helped me realize when you look at wildlife pictures, when you see those close ups, they’re rarely of animals in the wild.

Today wildlife photographers have a greater opportunity to capture animals in and around Marquette. For instance, there is currently a fox population in town, some of which are cross-foxes or part melanistic. A growing local moose population thanks to the introduction of moose in the Western UP in 1985 and ’87 also gives photographers more wildlife to capture.

Steve Lindberg has been interested in photography for a long time but only after retiring as a state representative did he pursue it. In 2013 he took his new camera and dog out for a walk and posted a picture on his Facebook page. That has remained his daily routine: getting outside, taking pictures of wildlife, and sharing a photo. At the History Center for December 2020 and January 2021 we had a 43 minute narrated wildlife photography slide show program by Steve on rotation for viewing by the public. That is now available for you to access here.

Scot Stewart has also seen wildlife photography change though technology and communication. In the past, if someone found an unusual bird or animal, only one person might see it. With changes in communication, now many people can see and photograph it. Before the internet was commonly used, Scot recalls the phone being used with success at least one time. Marquette birders, through the Audubon Club, had a hotline which people could use to pass on information on local bird sightings: I discovered a Boreal Owl in my backyard. On that particular late afternoon [they] made enough phone calls that I had a single file line of about a dozen people in backyard that wanted to see it. Scot Stewart

Not only can more people see these birds, but people can come from further away thanks to today’s technology: There was a Western Tanager that was found in a mountain ash tree in Munising a couple years ago. Within two hours, there were birders from Sault, Canada that were there to see this bird. Scot Stewart

I had an opportunity a couple of times, in the springtime, to explore their dens. One year, they had a den that was about 24 feet long and dropped down between three and four feet. Their pups were born usually the first week of May. So, it was still a time when there was frost on tree roots and things like that but I crawled down a couple times into wolf dens and would take my flashlight and then a bag with my camera and flash in it because it didn’t fit. I dragged the thing through and literally kind of crawled on my belly down these twenty some feet while Jim stood at the top of the opening, and got down to where the pups were and took pictures of the pups. Had a chance to really get to know how the wolves behaved. Eventually we had to pass them on to another location but it was just a phenomenal opportunity to photograph. It helped me realize when you look at wildlife pictures, when you see those close ups, they’re rarely of animals in the wild.

Today wildlife photographers have a greater opportunity to capture animals in and around Marquette. For instance, there is currently a fox population in town, some of which are cross-foxes or part melanistic. A growing local moose population thanks to the introduction of moose in the Western UP in 1985 and ’87 also gives photographers more wildlife to capture.

Steve Lindberg has been interested in photography for a long time but only after retiring as a state representative did he pursue it. In 2013 he took his new camera and dog out for a walk and posted a picture on his Facebook page. That has remained his daily routine: getting outside, taking pictures of wildlife, and sharing a photo. At the History Center for December 2020 and January 2021 we had a 43 minute narrated wildlife photography slide show program by Steve on rotation for viewing by the public. That is now available for you to access here.

Scot Stewart has also seen wildlife photography change though technology and communication. In the past, if someone found an unusual bird or animal, only one person might see it. With changes in communication, now many people can see and photograph it. Before the internet was commonly used, Scot recalls the phone being used with success at least one time. Marquette birders, through the Audubon Club, had a hotline which people could use to pass on information on local bird sightings: I discovered a Boreal Owl in my backyard. On that particular late afternoon [they] made enough phone calls that I had a single file line of about a dozen people in backyard that wanted to see it. Scot Stewart

Not only can more people see these birds, but people can come from further away thanks to today’s technology: There was a Western Tanager that was found in a mountain ash tree in Munising a couple years ago. Within two hours, there were birders from Sault, Canada that were there to see this bird. Scot Stewart

Equipment, communication through the internet, and the ease of digital photography have all changed wildlife photography in the last few decades according to Scot: I think the biggest [change] is just in equipment. Everybody’s got equipment now that’s really superb, it’s lightweight, there’s some brands that are incredibly good and don’t need tripods or anything with long telephoto lenses. So that’s made it a lot easier to really get great shots. The accessibility, knowing where things are through the internet and cell phones and that sort of thing, has helped a lot. The other thing is just digital photography and being able to look at what you’re shooting and see right away what kind of results you’re getting has been just huge. You’d take a bunch of pictures and get back, get something wrong and nothing is there, now you don’t have those same problems. Scot Stewart

Scot credits the community of local birders with sharing opportunities: I think one of the best things that has come along for wildlife photographers is just the community of birders in Marquette today. We have one of the highest concentrations of amazingly qualified and well communicating birders of any place that I know. Scot Stewart

Photography has helped local people and tourists alike realize what a beautiful place this is. I think it’s helped people realize just what a spectacular place the Upper Peninsula is. You know besides the wildlife, the scenery in which to view the wildlife. [Tourists] come up here and just discover what a phenomenal place it is. Scot Stewart

In thinking of the future, Scot worries that “the success of the place is often its greatest threat.” He gives an example of a paddler traveling around Lake Superior in the 1970s who asked Scot to travel with him to take pictures for a book. After the trip was done, the paddler decided against the book. He worried if he published about these places, whether it was a beautiful place to camp, or a great place to fish, that everyone would go there and ruin it. However, Scot thinks photography can help us with preservation and conservation: I believe that photography may be one of the best ways to help people see just how important it is to keep things in the state they are, in as many places as possible. So that the next generation, and the generation after that can follow and enjoy it the same way that we do today. Scot Stewart

Scot credits the community of local birders with sharing opportunities: I think one of the best things that has come along for wildlife photographers is just the community of birders in Marquette today. We have one of the highest concentrations of amazingly qualified and well communicating birders of any place that I know. Scot Stewart

Photography has helped local people and tourists alike realize what a beautiful place this is. I think it’s helped people realize just what a spectacular place the Upper Peninsula is. You know besides the wildlife, the scenery in which to view the wildlife. [Tourists] come up here and just discover what a phenomenal place it is. Scot Stewart

In thinking of the future, Scot worries that “the success of the place is often its greatest threat.” He gives an example of a paddler traveling around Lake Superior in the 1970s who asked Scot to travel with him to take pictures for a book. After the trip was done, the paddler decided against the book. He worried if he published about these places, whether it was a beautiful place to camp, or a great place to fish, that everyone would go there and ruin it. However, Scot thinks photography can help us with preservation and conservation: I believe that photography may be one of the best ways to help people see just how important it is to keep things in the state they are, in as many places as possible. So that the next generation, and the generation after that can follow and enjoy it the same way that we do today. Scot Stewart

Thank you to all who contributed photographs to be used in this exhibit. Historic photographs are from the J.M. Longyear Research Library at the MRHC.